Origin Of Thanksgiving

“O that men would praise the LORD for his goodness, and for his wonderful works to the children of men!” -Psalm 107:8, 15, 21 and 31

For Christians, Thanksgiving means more than just turkey and football. Most of us have a vague notion that this holiday began when the Pilgrims invited their Indian neighbors to dinner to thank God for his provisions. But there really is much more to the story.

The Atlantic crossing in the fall of 1620 had been an extremely difficult journey for the Pilgrims. For two months, 102 people were wedged into what was called the “’tween decks”—the cargo space of the boat, which only had about five-and-a-half feet of headroom. No one was allowed above deck because of the terrible storms. This was no pleasure trip, but only one person died during the voyage.

The Pilgrims had comforted themselves by singing the Psalms, but this “noise” irritated one of the ship’s paid crewmembers. He told the Pilgrims he was looking forward to throwing some of their corpses overboard after they succumbed to the illnesses that were routine on such voyages. But as it turned out, this crewmember himself was the only person on the voyage to become sick and be thrown overboard. God providentially protected His people. A little-known fact about the Mayflower is that this ship normally carried a cargo of wine; and the wine spillage from previous voyages had soaked the beams, acting as a disinfectant to prevent the spread of disease.

During one terrible storm, the main beam of the mast cracked. Death was certain if this beam could not be repaired. At that moment, the whole Pilgrim adventure could very easily have ended on the bottom of the Atlantic. But, providentially, one of the Pilgrims had brought along a large iron screw for a printing press. That screw was used to repair the beam, saving the ship and all on board.

After sixty-six days at sea, land was sighted off what is now Cape Cod, Massachusetts. But that was not where the Pilgrims wanted to be. They had intended to establish their new colony in the northern parts of Virginia (which then extended to the Hudson River in modern-day New York), but two factors interrupted their plans. The winds had blown them off course, but they also learned that some other Englishmen who wanted to settle in the same northern part of Virginia had bribed the crew to land them somewhere else.

Once again God was in charge and the Pilgrims were right where God wanted them to be. Had they actually landed near the Hudson River, they would have most certainly been attacked by hostile Indians. Instead, there were no Indians on Cape Cod when the Pilgrims made landfall there.

Many years before some local Indians had captured a Frenchman on a fishing expedition in that region. Just as he was about to be killed, the Frenchman told the Indians that God would be angry with them, would destroy them all, and would replace them with another nation. The Indians boastfully told him that his God could never kill them. However, when the Pilgrims landed in that same region, the land had already been cleared and the fields had already been cultivated, but those Indians who had prepared the land had nearly all died of the plague a year or two earlier.

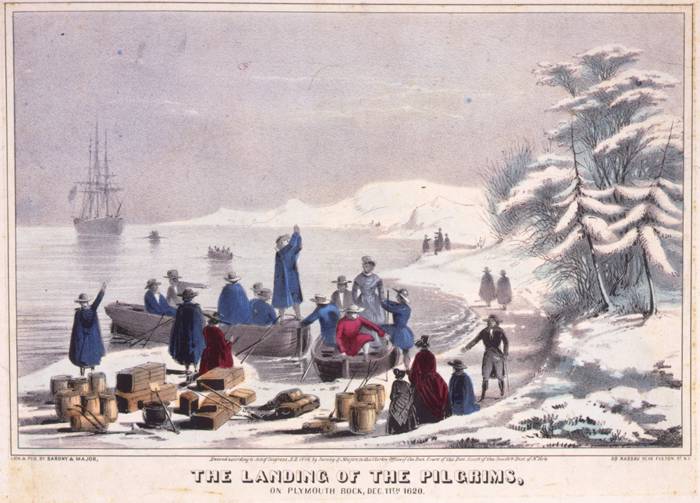

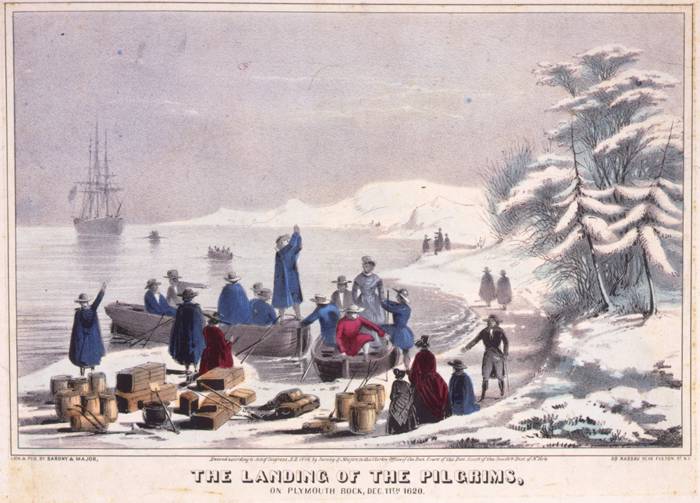

Despite this provision of safety from the Indians, the Pilgrims barely survived their first winter on the Cape. Only four families escaped without burying at least one family member. But God was still faithful. In the spring of 1621, He sent Squanto to them, an Indian who could speak their own language and who offered to teach them how to survive in this strange new land.

Squanto was one of the few Indians from that area who had not died of the plague. He had been captured as a young man and taken to England as a slave. During that time he mastered the English language; and then had been freed and returned to his native territory shortly before the Pilgrims arrived. Probably the most important thing Squanto taught the Pilgrims was how to plant the Indians’ winter staple crop—corn.

The Pilgrims thanked God for this wonderful helper, but they also shared with Squanto the most valuable treasure they had brought with them from England—the Gospel. Squanto died within a year or two after coming to the aid of the Pilgrims, but before his death he asked them to pray for him that he might go to be with their God in Heaven.

Other Indians who Squanto had introduced to the Pilgrims were also impressed with their God. During the summer of 1621, when it appeared the year’s corn harvest would not survive a severe drought, the Pilgrims called for a day of fasting and prayer. By the end of the day, it was raining. The rain saved the corn, which miraculously sprang back to life. One of the Indians who observed this miracle remarked that their God must be a very great God because when the Indians pow-wowed for rain, it always rained so hard that the corn stalks were broken down. But they noticed that the Pilgrim’s God had sent a very gentle rain that did not damage the corn harvest.

It was that same miraculous corn harvest that provided the grain for the Pilgrims’ first Thanksgiving meal with their Indian friends and helpers. Today, many of our public school children are taught that we celebrate Thanksgiving because the Pilgrims were thanking their Indian neighbors for helping them; but the evidence of history shows that on that first Thanksgiving Day the thanks of both Pilgrims and Indians went to God for His great goodness toward them all. But the story does not end there.

Even though the Pilgrims hosted the first Thanksgiving dinner in America, the holiday itself actually has its origins almost 170 years later, after the Revolutionary War had been won and our American Constitution had been adopted. In 1789, Congress approved the Bill of Rights, the first 10 Amendments to the Constitution. Congress then “recommended a day of public thanksgiving and prayer” to thank God for blessing America. President Washington declared November 26, 1789, as the first national day of prayer and thanksgiving to the Lord.

Another 75 years later, after the Civil War ended, President Abraham Lincoln established the last Thursday in November as a day to acknowledge “the gracious gifts of the Most High God” bestowed upon America. Every president did the same until 1941 when Congress officially made Thanksgiving a national holiday.

Now that you know the true story, this Thanksgiving make sure that your children learn it too. Let us all join with generations of Americans before us in giving thanks to God for blessing our country.