|

PROFIT in the pulpit Reprinted from the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, 3/02/2003

Mike Murdock peers into the television camera, seemingly able to see the people watching him. He says he can sense that the poor, the struggling and the lonely have tuned in to his program. "You've got to have a breakthrough," he tells them. Murdock offers the solution to all their problems: Give money to a man of God. Murdock's unwavering message – on his program, at his seminars and in his books – is the Law of the Seed: Plant a seed and reap a harvest from God. The seed can be time, patience, love. But Murdock specializes in encouraging people to give money. In return, Murdock promises, God will restore relationships, heal the body and provide financial salvation. The reward will be 100 times the gift. All of the money, the Denton televangelist says, allows the Mike Murdock Evangelistic Association to spread the Gospel to the four corners of the earth. "If any of this money is for Mike Murdock's personal gain," he often says, "may a curse be upon me and my ministry and may my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth." But a six-month Star-Telegram examination shows that the ministry, which Murdock founded as a nonprofit corporation, spends more than 60 percent of its revenue on overhead. Though Murdock says he despises poverty, the ministry's spending for needy families and benevolence is minuscule. For nearly a decade, less than 1 percent of donors' money has been used for such charitable works. On the other hand, the ministry pays Murdock, its 56-year-old president and director, a salary that has helped him maintain a lavish lifestyle that includes Rolex watches, expensive sports cars and exotic animals. In 2000, $3.9 million poured into the ministry, though Murdock's pitch is typically for small amounts. Send $31 a month or $58. Donate $1,000 to "break the back of poverty," he says. Give sacrificially. "You say, 'Mike ... what if I don't have it?' " Murdock says during a November broadcast of his weekly television program Wisdom Keys. God will provide, Murdock answers. Give the money anyway. "Take a step of faith," he says. Murdock has slipped in and out of the public's attention. He made a splash in the early 1980s on The PTL Club television program with Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker. Murdock, untouched by PTL's collapse in scandal, developed his own television ministry. Today, he still frequents the programs of more-successful televangelists, such as faith healer Benny Hinn. In Texas, the public briefly took notice of Murdock's operations in 1998 after a string of women arrived in Argyle believing that he would marry or employ them. Murdock says he misled no one. He later moved the headquarters from Argyle to Denton, where he resumed a largely anonymous local existence. He is detached from the community even as he reaches millions of people through his books, his seminars and Wisdom Keys, seen in at least 50 communities. Though it's unclear how many viewers tune in, the ministry recently bought time on the Black Entertainment Television network, which Murdock said gives the show a potential viewership of 72 million households. Murdock would not agree to an interview with the Star-Telegram unless everything he said was printed verbatim. The televangelist labels as "satanic" anyone who examines the ministry's operations. And if others question his extravagant lifestyle – or compare it with the humble existence of some of the ministry's staff members – he says they are attacking his theology. Since the Star-Telegram began to examine the ministry, Murdock has shaken it up. He recently announced that his brother John Murdock left the board after years and was replaced by ministry staff pastor Dean Holsinger. Mike Murdock fired the ministry's accountants of about 10 years – Doris and James Couch. Doris Couch also left the board. Murdock hired new accountants and an attorney experienced in nonprofit organizations and asked for an audit of his operations. In December, Murdock sent letters to those on the ministry's mailing list, saying the association was supporting 1,000 children in Mexico. On his TV show, he started talking more about the luxuries at his disposal. He also began explaining his background, such as why "Dr. Mike Murdock" left Southwestern Assemblies of God University in Waxahachie before receiving a degree. Recently, on an audiocassette offered to donors, Murdock acknowledged that some ministry paperwork contained errors. On the tape, The School of Adversity, he blamed the staff for not carrying out his orders. "What I'm finding out as I travel around the world is that an instruction I gave to somebody three months ago was never followed," Murdock said. The ministry's new attorney, Philip S. Haney of Tulsa, Okla., and new accountants, Chitwood & Chitwood of Chattanooga, Tenn., attributed any problems that might have existed to the former accountants. Some financial information was reported incorrectly to the Internal Revenue Service, said John Walker of Chitwood & Chitwood, who had reviewed only the ministry's most recent data. But the Couches, not Murdock, made the mistakes, Walker said. Murdock doesn't understand such things, Walker said, even though Murdock has written a book for young ministers about how to incorporate and run a ministry and has attended workshops on nonprofit organizations. "He's just going to be kind of like a total innocent dumb preacher," Walker said. "When it comes to this stuff, he's dumb. If you ask him a question, he doesn't know." The ministry released its IRS filings as required by the federal law governing tax-exempt organizations. But staff members have refused to make public its books and financial records as required by the state law governing nonprofit corporations. The accounting firm and the attorney promised to provide the Star-Telegram with any information they had about how the ministry operates. They never did. Murdock likes to describe himself as a "Wal-Mart guy." But a $25,000 Rolex adorns his wrist. And he can shoot hoops on the "NBA-style" basketball court at his estate or take notes with a $4,500 fountain pen. Details of Murdock's lifestyle were pieced together from documents obtained by the Trinity Foundation, a televangelist watchdog group in Dallas; Denton County property-appraisal records; a report of a burglary at his home; interviews; and excerpts from his broadcasts and books. They show a man living a Hollywood lifestyle. Murdock says he drives a BMW 745, which typically sells for $69,000 to $75,000. He used to prefer driving a Porsche to the ministry. He has had at his disposal a ministry Corvette, Jaguar and Mercedes, Lincoln Continentals and, since August, a corporate jet valued at $300,000 to $500,000. Murdock lives in a Spanish-style, 3,177-square-foot adobe house that he calls Hacienda de Paz – or "House of Peace." He, not the ministry, owns it.

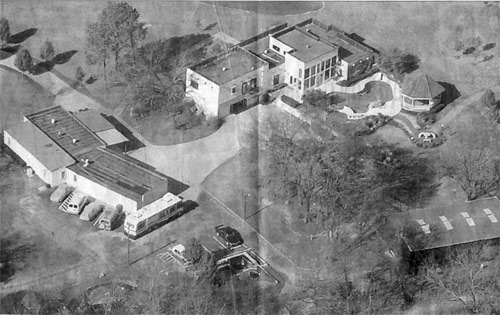

Few get a good view of the estate. It is protected by a black wrought-iron fence. The gates are monogrammed with two M's – his initials. On the well-kept grounds, a path winds near a tennis court and two of at least four gazebos on the property. At various times, Murdock has had a camel, an antelope, a donkey, ducks, geese, a lion and dogs. Near one edge of his property, he once kept llamas in a paddock. He has also had koi and catfish at the estate. He had 24 speakers wired in trees so he could hear gospel music everywhere on the grounds, he said during a 1998 broadcast. Inside his home, Murdock has had several fish tanks, including a large saltwater aquarium. In the gym, Murdock can work out with his personal trainer. He can relax in front of his home theater or in a Jacuzzi. And he can enjoy the fountains in his pool and living room. Murdock once kept coin and jewelry collections valued at $125,000. He reported the information to the Denton County Sheriff's Department after a theft. Sheriff's spokesman Kevin Patton said investigators dropped the case because Murdock would not list what had been stolen. Murdock has a second Rolex watch, besides the $25,000 one he often wears, he said during an appearance Oct. 19 in Grapevine. He didn't state its value. Murdock has said he was given the watches, expensive suits, several Chevrolet Corvettes, the BMW and a rare Vetta Ventura sports car – one of 19 made.

Financial records, however, indicate that his lifestyle could also be the result of the handsome salary he draws from the nonprofit ministry. On the cool, wet day he spoke in Grapevine, Murdock sighed as he lamented the hours he works. "After this kind of week, I'm ready to get a raise," he said. "I [was] figuring out the other day what I get paid for by the hour," Murdock said. "And, and I'm not doing well. I'm not doing well, getting paid for the hours I work." Murdock does not tell his audience how much he is paid, an examination of more than 10 of his books and a cross section of his TV broadcasts and ministry mailings found. But IRS documents filed by the ministry say he averages 40-hour workweeks. He received more than $242,000 – $104,819 in pay and $138,000 in benefits or deferred compensation – in 2000. That year's form listed no expense account for Murdock. That put him above the 90th percentile of managers of similar-sized nonprofit groups, according to GuideStar, a national database operated by the Philanthropic Institute, a nonprofit organization in Williamsburg, Va., that collects IRS data about charities. Murdock receives about $100,000 more in compensation, benefits and expenses than nearly 6,000 executives who oversee similar-sized nonprofit charities, according to a salary survey conducted by GuideStar. His salary soared in the 1990s. From 1983 to 1985, he received an average of $27,912 a year and had no expense account or benefits. That salary was 3.6 percent of the ministry's revenue. From 1993 to 2000, IRS records show his compensation package averaged $241,685 a year, or about 9 percent of the $21,040,299 the ministry took in during that period. The ministry's 2001 IRS form was not available because the association sought additional time to file it. Walker said last month that he could not recall Murdock's current salary. From 1997 to 1999, he drew from a $138,000 annual expense account, although records show that the ministry directly paid some of his expenses, including some travel. By comparison, in 2000, the combined expense accounts for the chief executive officers or directors of the five largest Christian nonprofit organizations – who oversaw a collective $1.5 billion in revenue – was $25,671. In 2000, Millard Fuller, president and CEO of Habitat for Humanity, oversaw an organization with $165 million in revenue and was paid $79,800 – $76,000 in salary and $3,800 in contributions to a benefit plan. If he had taken home the same percentage of revenue that Murdock did that year, Fuller would have earned an extra $10 million.

The IRS requires that the compensation of managers of nonprofit groups be reasonable, but it does not define reasonable. Determining what reasonable means is difficult, said Thomas Wolf of Wolf, Keens & Co., a consulting firm in Cambridge, Mass., that specializes in nonprofit corporations. "There are people who make a lot of money in the nonprofit world," said Wolf, author of Managing a Nonprofit Organization in the 21st Century.

Typically, trustees have the final say-so in approving the manager's compensation. But Murdock's father and brother, who served on the board, told the Star-Telegram that they did not know his salary. For the past two years, Murdock's salary, as well as salaries of other high-level employees, was set by an outside firm, according to Walker, who couldn't recall its name. That raises the issue of who approved Murdock's salary if the board did not. "That's a conflict of interest of the highest order if nobody decided besides him whether that's fair or not," said Dan Busby, vice president of donor services for the Evangelical Council for Financial Accountability, a kind of Christian Better Business Bureau. Early in his ministry, the Rev. Billy Graham relinquished control to a board of directors to help ensure that there would be no conflicts of interest. Graham is a charter member of the evangelical council. In 2000, he received $197,911, including benefits and an expense account, for his work as chairman of the ministry, according to the organization's IRS forms. The ministry's revenue that year was $125 million. While Murdock preaches that ministry employees should prosper, his staff does not share in the abundance. No one earns more than $50,000 a year, according to the most recent IRS forms. Federal and county records show that some ministry employees live in manufactured homes valued at less than $50,000 that they rent or have bought from the ministry. Other longtime employees have lived in apartments. In 1998, when Murdock received $199,784 in salary and $138,000 in expenses, the ministry told at least four employees that it could not pay overtime, according to a memo dated June 17, 1998. The ministry's management decides the pay for low-level employees, Walker said. Ole Anthony, the founder and president of the Trinity Foundation, said Murdock is living a double standard. "He tells his employees they should sacrifice, but he doesn't," Anthony said. "He tells the viewers to buy his books and give to him, but he doesn't give. He's just another cog in the wheel [of televangelism], maximizing self-interest." Murdock himself seems to knock ministers whose generosity ends at their own doorsteps. Ministers have a duty to make sure their staff prospers, he wrote in his book The Three Most Important Things in Your Life. "So, while he enjoys the beautiful luxury of his million dollar home, thousands sit under his ministry who can hardly make their car payment," Murdock wrote. "Their homes are tiny, cramped and uncomfortable." John Murdock said having wealth has made his brother a target. A childhood of poverty, spent largely in Lake Charles, La., taught his brother that a ministry needs money to do the most good, John Murdock said. "Now it's up there where it looks like – 'Well, let's look at this. He shouldn't be making money like that,' " he said. "Why shouldn't he? We understand it with everybody else." In 2000, Jeff Leva trusted Mike Murdock enough to pledge $1,000 to the ministry. The 32-year-old Bedford resident, who is studying to be a minister, said Murdock's teachings have blessed his life. Leva said he found a job 45 to 60 days after making the donation. He was sure Murdock used the donation to spread the Gospel. But he did not know specifically how the ministry spends its money. So what happened to the $1,000? Here's what, according to the ministry's IRS forms for 2000: About $623 would have helped pay the ministry's operating costs. About $255 would have gone toward program services – the ministry's mission of spreading the Gospel. About $117 would have been deposited in the ministry's bank account. And about $4 would have been used for what were reported as fund-raising expenses. On IRS forms for the five most recent years available, the Mike Murdock Evangelistic Association has reported spending about a quarter of its revenue on program services. But much of that was spent to cover the cost of producing books, cassettes and the television program – all of which contained prolonged appeals for money. The ministry didn't classify these expenses as fund-raising costs. As with other expenses, it's up to the preparer to decide what constitutes a fund-raising cost. The ministry's operating costs, which include salaries, supplies, telephones, facilities and printing, consumed about 62 percent of its revenue – far more than what is recommended by several groups that analyze nonprofit organizations' spending. The ministry's finances did not always lean so heavily toward overhead costs. From 1983 to 1985, spending on program services hovered near 58 percent of revenue. Busby, of the Evangelical Council for Financial Accountability, said most organizations in the council spend about 80 percent of their budgets on program services. Among nonprofit corporations with similar purposes, the Murdock ministry falls into the bottom 10 percent for program-services spending, according to an analysis that the Star-Telegram paid GuideStar to conduct. For a comparison, consider Wycliffe Bible Translators, an organization in Orlando, Fla., that translates the Bible into "all of the languages where it is needed." In 2000, its budget was $111 million. It spent about 11 percent on overhead and about 5 percent on fund raising. Eighty-four percent went to program services. The World Bible Translation Center in North Richland Hills spent $2,679,463 in 2000, according to the organization's IRS form. It spent about 10 percent on salaries and management, 10 percent on fund raising and 80 percent on program services. Such comparisons are a point of contention among nonprofit organizations, said Chris Hempe, president of MinistryWatch, a watchdog group in Matthews, N.C. IRS instructions say nothing about what constitutes a program-services expense, so it is left to the preparers to decide, Hempe said. "This obviously leaves a lot of room for interpretation and will be unique for every organization," he said. Busby, who reviewed the Murdock ministry's 2000 IRS form at the Star-Telegram's request, said the association has either spent poorly or not considered how the figures will be perceived. The ministry's program-services expenses "would often raise the question in donors' minds concerning the proper use of their donations," Busby said. Several accountants who reviewed the ministry's IRS filings agreed with Busby's assessment. Wolf said some nonprofit "industries," such as symphony orchestras, set standards. "You have to know more about the specific services being provided – how expensive it is to provide that service and how the people are accounting for it," he said. How and why the ministry chose to account for the money as it did are secrets. The Couches, who were also fired as Murdock's personal accountants, declined to talk. But their son, Craig Couch, said comparisons involving the ministry's spending are inappropriate because of the subjectivity of reporting expenses. Couch said that if Murdock was traveling to a church to speak, airfare might be written as a management expense because his traveling was not in itself a program service. He said he did not know why ministry expenses were categorized as they were on the forms. But he said the IRS has never questioned them. Walker said the Couches made mistakes in allocating expenses. Leva's faith in Murdock was unbowed when he learned about the ministry's spending. "If I believe in Mike Murdock, as I do, I'm not going to worry about the numbers," he said. "... It sounds like a majority of that money was re-established into his ministry." But count Evelyn Marie Hill of Buffalo, Mich., among the doubters. She groups Murdock with a number of prosperity teachers who she believes took advantage of her daughter's pain and uncertainty to make a buck. Hill's daughter, Pamela Hill, who is now deceased, had gone through a divorce and was trying to raise a son by herself, her mother said. After her daughter began giving to ministers including Murdock, Evelyn Hill had to help support her daughter and her grandson. "Yet they're living high on the hog," Hill said. " ... They have to have their private planes to fly here and there." Murdock's eyes flinch and close in lamentation. He tells Wisdom Keys viewers that he has seen suffering orphans in Manila, Philippines, and Puerto Vallarta, Mexico. "I'm right now researching a new part of our ministry I'm excited about a lot," he said on the Jan. 21 show. "I've always wanted to have an orphanage, from the time I was a kid."

The ministry is apparently in good financial health. For most of the 1990s, it received more money than it spent. At the same time, its support of the needy was less than 1 percent of revenue, according to IRS forms. In 2000, when the ministry received $3,858,637, it spent $2,056 on "needy families and benevolence." That same year, it spent $65,348 on flowers and gifts. At year's end, the ministry had $451,805 more revenue than expenses, money that a nonprofit group can use to build reserves or save for other purposes. The ministry's giving that year was not an anomaly. In 1999, the ministry spent $24,990, but that amount still represented a tiny part of its revenue – $2,955,011. In 1998, it spent $2,257 on "needy families and benevolence" out of $2,644,681 in revenue. The IRS reports aside, friends and relatives say Murdock has always given generously to others. John Murdock said his brother has put much of what he has made back into the ministry. "He's given lots of money to people you'll never know about," he said. Mike Murdock has said the ministry gives money to the Marion Zirkle Children's Ministry, which operates a children's foundation in Guatemala. Apparently, that is the ministry listed on the IRS forms as "the Marion Zirkie Ministry." In 2000, the Mike Murdock Evangelistic Association allocated $2,700 to the children's ministry; in 1999, $625; and in 1998, $700. Some of the other ministries or churches listed as having received allocations said the money was for services provided. Others said it was a gift. Thomas De La Garza, whose ministry is listed as having received $14,000 in 2000, said he was personally paid the money for singing and appearing at seminars. Also on the list was Murdock's father, who was shown as having received $13,250 in 2000. David Holton, a childhood friend, said that about 18 years ago, Mike Murdock telephoned him unexpectedly and gave him $5,000. Holton said he did not know whether the money was from Murdock or the ministry. "I hadn't seen him in 12 years," said Holton, who is the pastor of an International Pentecostal Holiness church in Jonesboro, La. "I hadn't even talked to him. He just felt impressed to do it." At the time, Holton said, he was struggling with debt and trying to start a church. "He set me back on my feet again," Holton said. "He's done that for more than one person, probably a lot of people." Murdock has no time for critics, he often says. They despise his decisions because they disagree with his goals, he says. And paperwork is useless in testing whether an organization or a person is trustworthy, he says. "You can't prove integrity. You can't prove integrity. It has to be discerned." True to his word, he said he had no time to discuss the ministry's finances or its work. But Murdock says he is not responsible for the accuracy of information prepared by others at the ministry. At the "School of Wisdom" seminar in October, he seemed to distance himself from the ministry's finances, saying accountant Doris Couch had overseen them. "Her and her CPAs, they know more about my money than I do," he said. The ministry's new accounting firm paints a similar picture. Walker said Murdock has had limited control over the ministry's finances. Walker also said that Couch had signed all the ministry's checks and that Murdock had nothing to do with them. But Craig Couch said the only checks his mother signed were for payroll. "I would say that, in a general sense, anyone is accountable for their own organization," Couch said. "... Whether it's for Mike Murdock or any of our accounting clients, we give that information to them. They certainly have a responsibility [to make sure] the information is true and accurate." Ministry memos indicate that Murdock signed off on at least some expenses and was constantly informed about nearly every aspect of operations. On April 30, 1998, then-general manager Matti Cook-Smith wrote to Murdock that she "met with [ministry bookkeepers] ... and dictated memo concerning checks being authorized by you or I before being issued and issuing expense check to person doing spending." An organization's trustees are ultimately responsible for information submitted to the IRS, Wolf and others said. Mike Murdock; his father, the Rev. J.E. Murdock; and his brother John Murdock served as trustees of the Mike Murdock Evangelistic Association for the past several years – sometimes as the only ones. Mike Murdock's signature is on the ministry's IRS forms. On a recent audiocassette, Murdock said his busy schedule had left him out of touch with the details of the ministry's operations. He said he had consulted with an accounting firm, which told him that the problems were merely a few words out of place on the IRS forms. "They said, 'Mike, this piece of information has not been entered on the right document. This is the wrong phrase for this. In fact, this particular word should not have been used,' " Murdock said. The public should be able to look at the ministry's financial statements to find out about its finances. According to Article 1396-2.23A of the Texas Non-Profit Corporation Act, "All records, books, and annual reports of the financial activity of the corporation ... shall be available to the public for inspection and copying ... during normal business hours." A corporation that fails to comply with this is guilty of a Class B misdemeanor. But the ministry has repeatedly refused to release the information. Haney, the ministry's tax attorney, said in December that the public is probably entitled to see the documents. Chitwood & Chitwood is auditing the ministry and trying to sort through other issues, Walker said. "We're going to clean this ministry out," he said last month. Once everything has been straightened out, the ministry's records will be released, Walker said. Some other religious nonprofit corporations pride themselves on providing financial information to donors. On the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association's Web site, a visitor can find detailed financial information, including its IRS forms and audited financial statements. The IRS does not require disclosure of the information, but the Evangelical Council for Financial Accountability requires its members to make it available. The Murdock ministry is not a member of the council. Murdock and his staff apparently view with suspicion anyone who asks to see financial documents. In an April 1997 newsletter, Murdock describes an incident in which a man tried to look at those documents at the ministry's headquarters. "I find it interesting, strange, significant ... and demonic," Murdock wrote. "... He left memories of rudeness and claimed, 'by law you can't refuse me anything I am asking for.' "... I believe there is no trap or pit Satan will not try to find ... to distract and break the focus of men of God of this generation." Murdock does not say whether the ministry complied with the man's request. During his Dec. 11 broadcast, Murdock seemed to take up the issue of financial disclosure. Critics might nitpick paperwork problems, he said, but his work is on a higher level than documentation. "Men of God can go on television and speak and preach and pour their hearts out and work, write books, trying to help people be conscious of God," Murdock said. "And you will have people try to find anything, any flaw. ... 'Did they make a mistake here? Did they file the wrong insurance papers, the wrong government papers? Did they hire somebody they shouldn't have hired? What did they do wrong?' " He said such adversaries create opportunities for the godly. "Without Goliath, David is just a shepherd boy," he said. Ministry's board had minimal roleBy Darren Barbee For the past several years, the governing board of the Mike Murdock Evangelistic Association has been made up of Mike Murdock, his father, a brother and, occasionally, people who worked for the ministry or who did business with it. But the board's mainstays – Murdock's father, the Rev. J.E. Murdock, and brother John Murdock – said they had little information about how the ministry operated. And in recent years, they said, they have rarely gathered for formal meetings. Neither knew who worked as the ministry's accountant or who served with them on the board. Both said Mike Murdock directed the ministry, with little formal action by the board. It's not always clear who the other board members were. There are differences between what the ministry reported on forms to the Internal Revenue Service and what was told to donors. The ministry's 2001 IRS forms are not available. All of that raises questions about the ministry's financial accountability, said Dan Busby of the Evangelical Council for Financial Accountability. A nonprofit corporation's spending decisions should start and finish with a strong, independent board, he said. "Lack of an independent board doesn't really give a donor much to put faith in," Busby said. Murdock himself has advised other ministers to emphasize financial accountability and board control. In his 1986 Young Minister's Handbook, he wrote: "There is far more to incorporating a ministry than ... drawing up bylaws and a statement of purpose for your ministry. You must have regular meetings with your board. You must keep your board members informed, keep a record of the minutes." The evangelical council requires each of its member organizations to be governed by a board of at least five people, the majority of whom should not be employees or relatives. The Mike Murdock Evangelistic Association is not a member of the council and has never applied for membership, according to the council. The council requires that boards meet at least semi- annually to establish policies and review the ministry's accomplishments. And trustees must examine an annual audit and maintain communication with the accountants. State legal requirements are less stringent. The Texas Non-Profit Corporation Act says nonprofit corporations must have at least three board members. The board must meet at least once a year. The law requires that the board "prepare and approve" an annual report of financial activity, which must conform to the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants' standards. At the federal level, the Internal Revenue Service mandates that all board members be listed on the corporation's IRS reports, regardless of whether they earn salaries. But it does not set a minimum number of board members, deferring to state laws, accountants said. According to bylaws that Murdock's ministry drew up in 1982, when it was based for a time in Norwalk, Calif., the board is supposed to have three to six members. J.E. Murdock, 86, said that while his son sometimes "counts me on the board," Mike Murdock makes all the decisions. John Murdock said that he has not been an active board member recently but that his brother had phoned him in the past to discuss ministry business. He could not remember when he last had such a discussion, he said. He did recall that his brother had tape-recorded some board meetings. John Murdock also said he didn't want to stand in the way of whatever his brother wanted the ministry to do. Obstinate board members keep things from getting done, he said. "As far as me telling him, 'You don't do that,' I don't think that's the proper way," he said. "I find that if you have somebody in the organization that's not a yes man, well, that impedes progress. "You can get so much more done with yes people. And don't misunderstand me there. ... I've been in some meetings where you could never conclude anything." The brother and father said they trusted Mike Murdock to run things properly. They said they were unfamiliar with the ministry's financial operations. They also didn't know the name of the ministry's longtime accountant and didn't know that she had served with them on the board. Doris Couch served with them for at least one year, 2000, according to IRS reports. She also listed herself as vice president of the ministry in documents filed with the Denton Central Appraisal District in 1997, although she is not listed as such on IRS documents filed that year. John Murdock said last summer that Couch's name only "sounds familiar." "I don't know hardly anyone on his staff," said John Murdock, who lives in Orange. "I'm six hours away." At least one other person may have served with them on the board: Frank Berry of Mobile, Ala. Neither John Murdock nor J.E. Murdock recognized Berry's name. Berry's company, the now-defunct Able Press, was the ministry's highest-paid contractor in 1998. That year, Berry's signature was on a letter asking the ministry's donors to make personal donations to Mike Murdock. Under his signature, Berry was described as "Board Member, Mike Murdock Evangelistic Association." The 1998 IRS form does not list Berry as a board member. It is unclear whether the form was incorrectly filled out or whether the letter misstated Berry's affiliation. In a phone interview in December, Berry said he could not remember the letter. "I know that they do letters like that," he said. "I don't remember that specific letter." When asked whether he was ever a board member, Berry said, "I don't think I want to answer that one." Failure to list board members on the form can lead to unspecified IRS penalties for the organization and the individuals responsible. However, Chris Hempe, president of MinistryWatch, said omitting a board member's name is not legally an egregious error unless a ministry has a reason for trying to conceal the relationship. The Murdock ministry's attorney said he did not know the board members' names. Philip S. Haney of Tulsa, Okla., who began representing the ministry in early November, said he had no information about Berry's role. He also didn't know whether the board kept minutes of its meetings. John Walker of the ministry's new accounting firm, Chitwood & Chitwood of Chattanooga, Tenn., said last month that he has seen board minutes but that they were not signed until recently. Berry's company worked with the ministry for several years. In 1998, the ministry paid Able Press $550,000. From 1997 to 2000, the printing company was paid more than $1.4 million, IRS records show. In 1997, Mike Murdock described Berry as one of his closest friends. Matti Cook-Smith, the ministry's general manager for much of the late 1990s, asked Murdock in a 1998 memo whether Berry and Couch were board members. She also asked Murdock whether she was a board member, according to documents gathered by the Trinity Foundation, a televangelist watchdog group in Dallas. IRS forms don't list her as a trustee. IRS forms from the early 1990s do list the Rev. LaVaughn Young of Charleston, S.C., and his daughter, Joy Potter, as trustees. Young said he did not participate in formal meetings and did not vote. "It was a title without a job," he said. Potter, who was also Murdock's assistant, declined to publicly comment. After the Star-Telegram began examining the ministry in July, Murdock shook up the board. On the audiocassette The School of Adversity, Murdock said the ministry had replaced John Murdock on the board. "My brother used to be a board member of our ministry," he said. "And then when he got so busy in his own business he couldn't come to any of the conferences, I said, 'That's all right, John. I'll have someone take your place. But I still want you to be on my circle of counsel.' " Serving in his place is Dean Holsinger, the ministry's staff pastor and Murdock's longtime friend. Holsinger said last year that he had attended at least one board meeting. But he declined to answer other questions, saying he had not been given the authority to speak to reporters. He would not say who could give him that authority. Walker said last month that the board will hold quarterly meetings until ministry records are straightened out. At an October seminar in Grapevine, Murdock explained how his board meetings work. He also told the crowd of about 300 how he had consulted with the board before the ministry bought a jet last summer. "I called one of my board members," he said. "I said, 'I want to talk to you. I want you to ... give me some feedback. What do you think?' And the board member said, 'You're running way late. You should have done this years ago. ...' "Now why? They understood my goals. My major goal is to spend time in [God's] presence and write what he tells me and mail it to everybody I know in the form of a book." |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

By Darren Barbee

By Darren Barbee

Craig

Couch, who works for the ministry's former accounting firm, said

that the association commissioned a salary survey in 2000 and that

Murdock's compensation was on a par with that of managers of other

nonprofit and for-profit corporations.

Craig

Couch, who works for the ministry's former accounting firm, said

that the association commissioned a salary survey in 2000 and that

Murdock's compensation was on a par with that of managers of other

nonprofit and for-profit corporations.  Murdock

began preaching in 1966 at age 19. The Mike Murdock Evangelistic

Association was established as a nonprofit organization in 1973 in

Lake Charles, La., by Murdock and then-wife Linda Murdock.

Murdock

began preaching in 1966 at age 19. The Mike Murdock Evangelistic

Association was established as a nonprofit organization in 1973 in

Lake Charles, La., by Murdock and then-wife Linda Murdock.