The Nation of Islam and

Malcolm X

The following quote is by Dr. Kenneth Boa Th. M.;

Ph.D.; D.Phil.

The Nation of Islam is undoubtedly the most

culturally significant sect of Islam in the United States. Popularly

known in earlier years as Black Muslims, the Nation of Islam is an

African-American cult that reinterprets Islam as a religion for the

oppressed Blacks. The original vision of its founder, Wali Fard

Muhammad, was of a separate and autonomous Black nation within the

United States. African Americans were urged to renounce their U.S.

citizenship and to reject their last names (which were their “slave

names”), using only “X” in their place. The most famous member of

the Nation of Islam, Malcolm X, was killed in 1965 by angry Nation

members after Malcolm had disavowed the group in favor of pursuing a

more traditional Muslim path. The Nation of Islam has been led since

the late 1970s by Louis Farrakhan, who emerged as the most controversial

African-American leader in the 1990s. Or to be more precise, a splinter group

of the Nation of Islam; the original group went through various name

changes and was absorbed into the world religion of (Sunni) Islam in

1985. Under Farrakhan, the Nation of Islam seeks economic

independence from the white establishment (“Buy Black”) rather than

political independence from the United States. He has provoked outrage over

the years for his rhetoric of hate, especially against the Jews. Still, for

many African-Americans Farrakhan’s message, especially his emphasis on

self-reliance, personal responsibility, and the importance of restoring

young Black men in America to their place in the home, strikes some

important and valid themes.

SOURCE: No God but Allah: Muslim Radicalism and the New

Islamic Sects, by Kenneth Boa Th. M.;

Ph.D.; D.Phil.

The Black Muslim Religion Exposed!

END

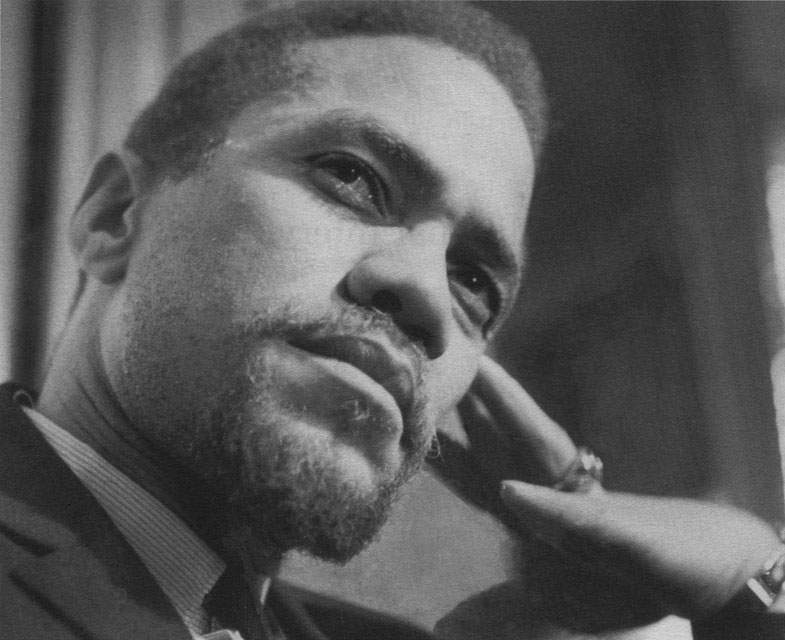

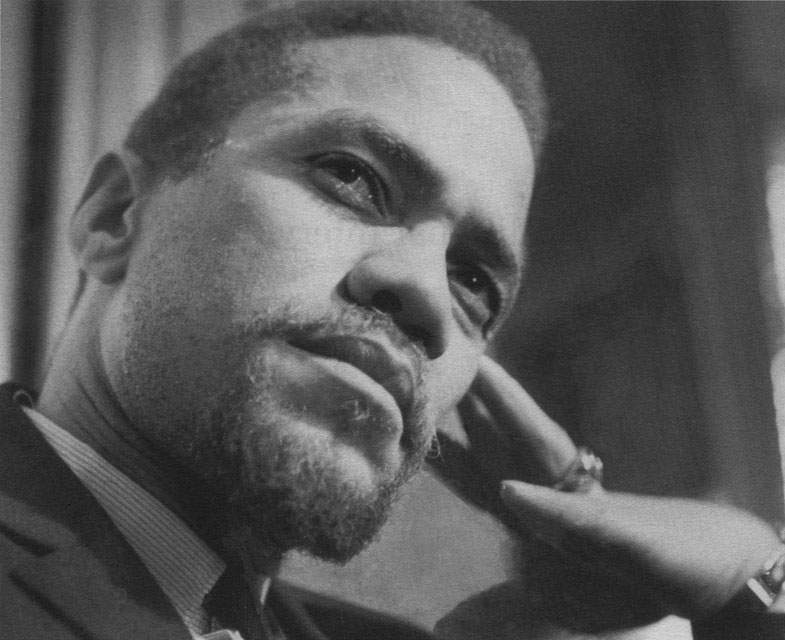

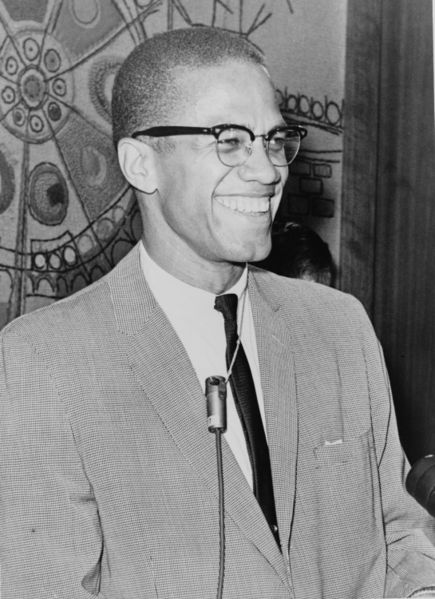

Malcolm X

human rights activist

Personal Information

Born Malcolm Little, May 19, l925, in Omaha, Neb.; died of gunshot wounds, February 21, 1965, in Harlem, N.Y.; son of Reverend Earl (a Baptist minister), and Louise Little; married wife, Betty (a student nurse), 1958; children; six daughters.

Religion: Muslim.

Career

Activist. Worker in Lost-Found Nation of Islam (Black Muslim) religious sect, 1952-64, began as assistant minister of mosque in Detroit, Mich., then organized mosque in Philadelphia, Pa., became national minister, 1963; established Muslim Mosque, Inc., founded Organization of Afro-American Unity in New York City, 1964; lecturer and writer.

Life's Work

"When I talk about my father," said Attallah Shabazz to Rolling Stone. "I do my best to make Malcolm human. I don't want these kids to keep him on the pedestal, I don't want them to feel his goals are unattainable. I'll remind them that at their age he was doing time." The powerful messages of Malcolm X, his dramatic life, and his tragic assassination conspire to make him an unreachable hero. Events in the 1960s provided four hero-martyrs of this kind for Americans: John F. Kennedy, Robert F. Kennedy, Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X. These idealistic men believed in the possibilities for social change, the necessity of that change, and the truth of his vision of change.

Of the four, Malcolm came from the humblest roots, was the most radical, most outspoken, and angriest--"All Negroes are angry, and I am the angriest of all," he often would say. The powerful speaker gathered huge crowds around him when he was associated with Elijah Muhammad's Lost-Found Nation of Islam movement, and afterwards with Malcolm X's own organization. Many Americans, white and black, were afraid of the violent side of Malcolm X's rhetoric--unlike Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s, doctrine of non-violent resistance, Malcolm X believed in self-defense.

But Malcolm X cannot be summed up in a few convenient phrases, because during his life he went through distinct changes in his philosophies and convictions. He had three names: Malcolm Little, Malcolm X, and El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz. Each name has its own history and illuminates a different facet of the man who remains one of the most compelling Americans of the 20th century.

Malcolm X's father was a Baptist minister and a member of the United Negro Improvement Association. Founded by Marcus Garvey, the group believed that there could be no peace for blacks in America, and that each black person should return to their African nation to lead a natural and serene life. In a parallel belief, Nation of Islam supporters in Malcolm X's time held that a section of the United States secede and become a nation onto itself for disenfranchised blacks. It seems possible that Malcolm X was predisposed to the separatist ideas of the Nation of Islam partly because of this early exposure to Marcus Garvey.

Malcolm X described in his autobiography (written with Alex Haley) the harassment of his father, including terrifying visits from the Ku Klux Klan; one of Malcolm X's first memories is of his home in Omaha burning down. The family moved to Lansing, Michigan, in 1929 and there Malcolm X's memories were of his father's rousing sermons and the beatings the minister gave his wife and children. Malcolm X believed his father to be a victim of brainwashing by white people, who infected blacks with self-hatred--therefore he would pass down a form of the abuse he received as a black man.

Malcolm X described in his autobiography (written with Alex Haley) the harassment of his father, including terrifying visits from the Ku Klux Klan; one of Malcolm X's first memories is of his home in Omaha burning down. The family moved to Lansing, Michigan, in 1929 and there Malcolm X's memories were of his father's rousing sermons and the beatings the minister gave his wife and children. Malcolm X believed his father to be a victim of brainwashing by white people, who infected blacks with self-hatred--therefore he would pass down a form of the abuse he received as a black man.

The minister was killed in 1931, his body almost severed in two by a streetcar and the side of his head smashed. In the autobiography, Malcolm X elaborated, saying that there were many rumors in Lansing that his father had been killed by the Klan or its ilk because of his

preaching, and that he had been laid on the streetcar tracks to make his death appear accidental. After his father was killed, the state welfare representatives began to frequent the house, and it seemed to Malcolm X that they were harassing his mother. Terribly stricken by her husband's death and buckling under the demands of raising many children, Louise Little became psychologically unstable and was institutionalized until 1963.

After his mother was committed, Malcolm X began what was to be one of the most publicized phases of his life. His brothers and sisters were separated, and while living with several foster families, Malcolm is began to learn to steal. In his autobiography, he used his own young adulthood to illustrate larger ideas about the racist climate in the United States. In high school, Malcolm began to fight what would be a lifelong battle of personal ambition versus general racist preconception. An English teacher discouraged Malcolm X's desire to become a lawyer, telling him to be "realistic," and that he should think about working with his hands.

Lansing did not hold many opportunities of any kind for a young black man then, so without a particular plan, Malcolm X went to live with his half-sister, Ella, in Boston. Ella encouraged him to look around the city and get a feel for it before trying to land a job. Malcolm X looked, and almost immediately found trouble. He fell in with a group of gamblers and thieves, and began shining shoes at the Roseland State Ballroom. There he learned the trades that would eventually take him to jail--dealing in bootleg liquor and illegal drugs. Malcolm X characterized his life then as one completely lacking in self-respect. Although his methods grew more sophisticated over time, it was only a matter of four years or so before he was imprisoned in 1946, sentenced to ten years on burglary charges.

Many journalists would emphasized Malcolm X's "shady" past when describing the older man, his clean-cut lifestyle, and the aims of the Nation of Islam. In some cases, these references were an attempt to damage Malcolm X's credibility, but economically disadvantaged people have found his early years to be a point of commonality, and Malcolm X himself was proud of how far he had come. He spared no detail of his youth in his autobiography, and used his Nation of Islam (sometimes called Black Islam) ideas to interpret them. Dancing, drinking, and even his hair style were represented by Malcolm X to be marks of shame and self-hatred.

Relaxed hair in particular was an anathema to Malcolm X for the rest of his life; he described his first "conk" in the autobiography this way: "This was my first really big step toward self-degradation: when I endured all of that pain [of the hair-straightening chemicals], literally burning my flesh to have it look like a white man's hair. I had joined that multitude of Negro men and women in America who are brainwashed into believing that the black people are `inferior'--and white people `superior'--that they will even violate and mutilate their God-created bodies to try to look `pretty' by white standards.... It makes you wonder if the Negro has completely lost his sense of identity, lost touch with himself."

It was while Malcolm X was in prison that he was introduced to the ideas of Elijah Muhammad and the Nation of Islam. Fundamentally, the group believes in the racial superiority of blacks, a belief supported by a complex genesis fable, which includes an envious, evil white scientist who put a curse on blacks. The faith became a focus for Malcolm X's fury about his treatment (and his family's) at the hands of whites, about the lack of opportunity he had as a young black man, and the psychological damage of systematic anti-black racism--that is, the damage of self-hatred.

Malcolm X read "everything he could get his hands on" in the prison library. He interpreted history books with the newly-learned tenets of Elijah Muhammad, and told of his realizations in an Playboy interview with Alex Haley. "I found our that the history-whitening process either had left out great things that black men had done, or the great black men had gotten whitened." He improved his penmanship by copying out a dictionary, and participated in debates in jail, preaching independently to the prisoners about the Nation of Islam's theories about "the white devil." The group also emphasizes scrupulous personal habits, including cleanliness and perfect grooming, and forbids smoking, drinking, and the eating of pork, as well as other traditional Muslim dietary restrictions.

When Malcolm X left prison in 1952, he went to work for Elijah Muhammad, and within a year was named assistant minister to Muslim Temple Number One in Detroit, Michigan. It was then that he took the surname "X" and dropped his "slave name" of Little--the X stands for the African tribe of his origin that he could never know. The Nation of Islam's leadership was so impressed by his tireless efforts and his

fiery speeches that they sent him to start a new temple in Boston, which he did, then repeated his success in Philadelphia by 1954.

Malcolm X's faith was inextricably linked to his worship of Elijah Muhammad. Everything Malcolm X accomplished (he said) was accomplished through Elijah Muhammad. In his autobiography, he recalled a speech which described his devotion: "I have sat at our Messenger's feet, hearing the truth from his own mouth, I have pledged on my knees to Allah to tell the white man about his crimes and the black man the true teachings of our Honorable Elijah Muhammad. I don't care if it costs my life." His devotion would be sorely tested, then destroyed within nine years.

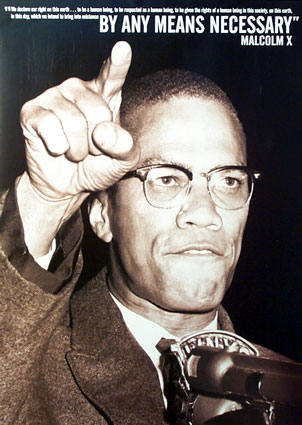

During those nine years, Malcolm X was made a national minister--he became the voice of the Nation of Islam. He was a speechwriter, an inspired speaker, a pundit often quoted in the news, and he became a philosopher. Malcolm used the teachings of the Nation of Islam to inform blacks about the cultures that had been stripped from them and the self-hatred that whites had inspired, then he would point the way toward a better life. While Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., was teaching blacks to fight racism with love, Malcolm X was telling blacks to understand their exploitation, to fight back when attacked, and to seize self-determination "by any means necessary." Malcolm spoke publicly of his lack of respect for King, who would, through a white man's religion, tell blacks to not fight back.

In his later years, though, Malcolm X thought that he and King perhaps did have the same goals and that a truce was possible. While Malcolm X was in the process of questioning the Nation of Islam's ideals, his beliefs were in a creative flux. He began to visualize a new Islamic group which "would embrace all faiths of black men, and it would carry into practice what the Nation of Islam had only preached." His new visions laid the groundwork for a break from the Black Muslims.

In 1963 a conflict between Malcolm X and Elijah Muhammad made headlines. When President John F. Kennedy was assassinated, Malcolm said that it was a case of "chickens coming home to roost." Rolling Stone reported that many people believed Malcolm X had declared the president deserving of his fate, when he really "meant the country's climate of hate had killed the president." Muhammad suspended Malcolm X for ninety days "so that Muslims everywhere can be disassociated from the blunder," according to the autobiography.

In 1963 a conflict between Malcolm X and Elijah Muhammad made headlines. When President John F. Kennedy was assassinated, Malcolm said that it was a case of "chickens coming home to roost." Rolling Stone reported that many people believed Malcolm X had declared the president deserving of his fate, when he really "meant the country's climate of hate had killed the president." Muhammad suspended Malcolm X for ninety days "so that Muslims everywhere can be disassociated from the blunder," according to the autobiography.

Muhammad had been the judge and jury for the Nation of Islam, and had sentenced many other Black Muslims to terms of silence, or excommunication, for adultery or other infractions of their religious code. Malcolm X discovered that Muhammad himself was guilty of adultery, and was appalled by his idol's hypocrisy. It widened the gulf between them. Other

ministers were vying for the kind of power and attention that Malcolm X had, and some speculate that these men filled Elijah Muhammad's ears with ungenerous speculations about Malcolm X's ambitions. "I hadn't hustled in the streets for years for nothing. I knew when I was being set up," Malcolm X said of that difficult time. He believed that he would be indefinitely silenced and that a Nation of Islam member would be convinced to assassinate him. Before that would come to pass, Malcolm X underwent another period of transformation, during which he would take on his third name, El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz.

A "hajj" is a pilgrimage to the holy land of Mecca, Saudi Arabia, the birthplace of the Prophet Muhammad; "Malik" was similar to Malcolm, and "Shabazz," a family name. On March 8, 1964, Malcolm X had announced that he was leaving the Nation of Islam to form his own groups, Muslim Mosque, Inc., and the Organization of Afro-American Unity. In an effort to express his dedication to Islam, and thereby establish a more educated religious underpinning for his new organization, Malcolm X declared he would make a hajj. His travels were enlarged to include a tour of Middle Eastern and African countries, including Egypt, Lebanon, Nigeria, and Ghana.

These expeditions would expand Malcolm X in ways that would have seemed incredible to him earlier. He encountered fellow Muslims who were

Caucasian and embraced him as a brother, he was accepted into the traditional Islamic religion, and he was lauded as a fighter for the rights of American blacks. "Packed in the plane [to Jedda] were white, black, brown, red, and yellow people, blue eyes and blond hair, and my kinky red hair--all together, brothers! All honoring the same God Allah, all in turn giving equal honor to the other." As a result of his experiences, Malcolm X gained a burgeoning understanding of a global unity and sympathy that stood behind America's blacks--less isolated and more reinforced, he revised his formerly separatist notions.

Still full of resolve, Malcolm X returned to the States with a new message. He felt that American blacks should go to the United Nations and demand their rights, not beg for them. When faced with a bevy of reporters upon his return, he told them, "The true Islam has shown me that a blanket indictment of all white people is as wrong as when whites make blanket indictments against blacks." His new international awareness was evident in statements such as: "The white man's racism toward the black man here in America has got him in such trouble all over that world, with other nonwhite peoples."

This new message, full of renewed vigor and an enlarged vision, plus the fact that the media was still listening to Malcolm X, was not well-received by the Nation of Islam. Malcolm X was aware that he was being followed by Black Muslims, and regularly received death threats. His home was firebombed on February 14, 1965--his wife and four daughters were unharmed, but the house was destroyed, and the family had not been insured against fire. It was believed that the attack came from the Nation of Islam. A week later, Malcolm X, his wife (pregnant with twin girls), and four daughters went to the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem, New York, where he would speak for the last time. A few minutes into his message, three men stood and fired sixteen shots into Malcolm X, who died before medical help could arrive. The three were arrested immediately, and were later identified as members of the Nation of Islam.

Malcolm X gave African-Americans something no one else ever had--a sense that the race has a right to feel anger and express the power of it, to challenge white domination, and to actively demand change. Politically sophisticated, Malcolm X told everyone who would listen about the tenacious and pervasive restraints that centuries of racism had imposed on American blacks. His intelligence and humility was such that he was not afraid to revise his ideas, and he held up the example of his transformations for all to see and learn from.

Although Malcolm X's own organizations were unsteady at the time of his death, the posthumous publication of his autobiography insures that his new and old philosophies will never be forgotten. In 1990, twenty-five years after his assassination, Malcolm X and his ideas were still a huge component in the ongoing debate about race relations. Plays and movies focus on him, new biographies are written, and several colleges and societies survive him. "Malcolm's maxims on self-respect, self-reliance and economic empowerment seem acutely prescient," said Newsweek in 1990. The words of Malcolm X and the example of his life still urge Americans to fight racism in all of its forms.

Works

Writings

-

(With Alex Haley) The Autobiography of Malcolm X, introduction by M.S. Handler, epilogue by Ossie Daivs, Ballantine Books, 1964.

-

Malcolm Speaks: Selected Speeches and Statements, edited with prefatory notes by George Breitman, Merit Publishers, 1965.

-

The Speeches of Malcolm X at Harvard, edited and with an introductory essay by Archie Epps, Owen, 1969.

-

Malcolm X Talks to Young People, Young Socialist Alliance, 1969.

-

Malcolm X and the Negro Revolution: The Speeches of Malcolm X, edited and with an introductory essay by Archie Epps, Owen, 1969.

-

Two Speeches by Malcolm X, Merit Publishers, 1969.

-

By Any Means Necessary: Speeches, Interviews, and a Letter by Malcolm X, edited by George Breitman, Pathfinder Press, 1970.

-

The End of White World Supremacy: Four Speeches, edited and with an introduction by Benjamin Goodman, Merlin House, 1971.

-

Work represented in anthologies, including 100 and More Ouotes by Garvey, Lumumba, and Malcolm X, compiled by Shawna Maglangbayan, Third World Press, 1975.

Further Reading

Books

-

(With Alex Haley) The Autobiography of Malcolm X, introduction by M.S. Handler, epilogue by Ossie Daivs, Ballantine Books, 1964.

-

McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of World Biography, McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1973.

-

Political Profiles: The Johnson Years, edited by Nelson Lichtenstein, Facts on File, 1976.

-

Political Profiles: The Kennedy Years, edited by Lichtenstein, Facts on File, 1976.

Periodicals

- Newsweek, February 26, 1990.

-

Playboy, January 1989.

-

Rolling Stone, November 30, 1989.

-

--Christine Ferran

END

Malcolm X

Malcolm X was a Nation of Islam minister and a black nationalist leader in the United States during the 1950s and 1960s. Since his assassination in 1965, his status as a political figure has grown considerably, and he has now become an internationally recognized political and cultural icon. The changes in Malcolm X's personal beliefs can be followed somewhat by the changes in his name, from Malcolm Little when he was a young man to Malcolm X when he was a member of the Nation of Islam to El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz-Al-Sabann after he returned to the United States from a spiritual pilgrimage to Mecca in 1964. He was a ward of the state, a shoe shine boy in Boston, a street hustler and pimp in New York, and a convicted felon at the age of twenty. After embracing Islam in prison and directing his grassroots leadership and speaking skills to recruit members to the Nation of Islam, he ultimately became an influential black nationalist during the civil rights movement of the 1960s.

The fifth child in a family of eight children, Malcolm was born May 19, 1925, in Omaha, Nebraska. His father, Earl Little, was a Baptist minister and a local organizer for the Universal Negro Improvement Association, a black nationalist organization founded by Marcus M. Garvey in the early twentieth century. His mother, Louise Little, was of West Indian heritage. Malcom's father was killed under suspicious circumstances in 1931 and his mother had a breakdown in 1937.

After his father's death and his mother's commitment to a mental hospital, Malcolm was first placed with family friends, but the state welfare agency ultimately situated him in a juvenile home in Mason, Michigan, where he did well. Malcolm was an excellent student in junior high school, earning high grades as well as praise from his teachers. Despite his obvious talent, his status as an African American in the 1930s prompted his English teacher to discourage Malcolm from pursuing a professional career. The teacher instead encouraged him to work with his hands, perhaps as a carpenter.

In 1941, shortly after finishing eighth grade, Malcolm moved to Roxbury, a predominantly African American neighborhood in Boston. From 1941 to 1943, he lived in Roxbury with his half-sister Ella Lee Little-Collins. He worked at several jobs, including one as the shoe shine boy at the Roseland State Ballroom. He became what he later described as a Roxbury hipster, wearing outrageous zoot suits and dancing at local ballrooms.

Malcolm moved to Harlem in 1943, at the age of eighteen. Here, he earned the nickname Detroit Red, because of his Michigan background and the reddish hue to his skin and hair. In his early Harlem experience, Malcolm was a hustler, dope dealer, gambler, pimp, and numbers runner for mobsters.

In 1945, when his life was threatened by a Harlem mob figure named West Indian Archie, Malcolm returned to Boston, where he became involved in a burglary ring with an old Roxbury acquaintance. In 1946 he was caught attempting to reclaim a stolen watch he had left for repairs, and the police raided his apartment and arrested him and his accomplices, including two white women. He was charged with larceny and breaking and entering, to which he pleaded guilty at trial. On February 27, 1946, he entered Charlestown State Prison to begin an eight- to ten-year sentence; he was twenty years old.

Malcolm was transferred in 1948 to an experimental and progressive prison program in Norfolk, Massachusetts. The Norfolk Prison Colony gave greater freedom to its inmates. It also had an excellent library, and Malcolm began to read voraciously. Prompted by his brother Reginald Little, Malcolm converted to Islam while in prison and became a follower of Elijah Muhammad, the leader of the Nation of Islam. The Nation of Islam, founded by Wallace D. Fard in the 1930s, advocated racial separatism and enforced a strict moral code for its followers, all of whom were African American.

Malcolm was paroled from prison in 1952. He immediately moved to Detroit, where he worked in a furniture store and attended the Nation of Islam Detroit temple. Malcolm soon abandoned the surname Little in favor of X, which represented the African surname he had never known. With his oratory skill, Malcolm X quickly became a national minister for the Nation of Islam. As a devout follower of Elijah Muhammad, he helped to establish numerous temples across the United States. He became the minister for temples in Boston and Philadelphia, and in 1954, he became minister of the New York temple. In 1958 he married Sister Betty X, who had earlier joined the Nation of Islam as Betty Sanders. Together, they had six children, including twins who were born after Malcolm's assassination.

During his early years with the Nation of Islam, Malcolm's primary role was as spokesman for Elijah Muhammad. He was a highly effective grassroots activist and successfully recruited thousands of urban blacks to join the organization. In 1959 a television program entitled The Hate That Hate Produced resulted in a focused public scrutiny of the Nation of Islam and its followers, who became known to many U.S. citizens as Black Muslims. Increasingly, Malcolm was seen as the national spokesman for the Black Muslims, and he was often sought out for his opinion on public issues. In vitriolic public speeches on behalf of the Nation of Islam, he described whites in the United States as devils and called for African Americans to reject any attempt to integrate them into a white racist society. As a Nation of Islam minister, he denounced Jews and criticized the more cautious mainstream civil rights leaders as traitors who had been brainwashed by a white society. He further challenged the so-called integrationist principles of recognized civil rights leaders such as Martin Luther King, Jr.

Elijah Muhammad took a somewhat less rash approach and favored a general non-engagement policy in place of more confrontational tactics. Malcolm's increasing popularity—as well as his caustic public remarks—began to create tension between him and Elijah Muhammad. Malcolm became frustrated at having to restrain his comments.

When President John F. Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963, Malcolm exclaimed that Kennedy "never foresaw that the chickens would come home to roost so soon." Malcolm later regretted his comment and explained that he meant that the government's involvement in and tolerance of violence against African Americans and others had created an atmosphere that contributed to the death of the president. Nevertheless, his comments and his increasing public notoriety prompted Elijah Muhammad to "silence" Malcolm and suspend him as a minister on December 1, 1963. Members of the Nation of Islam were instructed not to speak to him.

However, by 1963, Malcolm had become disillusioned by the Nation of Islam, particularly with rumors that Elijah Muhammad had been unfaithful to his wife and had fathered several illegitimate children. On March 8, 1964—while still under suspension from the Nation of Islam—Malcolm formally announced his separation from the organization. He soon announced the creation of his own organization, Moslem Mosque, Incorporated (MMI), which would be based in New York. MMI, Malcolm stated, would be a broad-based black nationalist organization intended to advance the spiritual, economic, and political interests of African Americans. On March 26, Malcolm met for the first and only time with the Reverend King, in Washington, D.C. King at the time was scheduled to testify on the pending Civil Rights Act of 1964.

In April 1964, Malcolm made a spiritual pilgrimage to Mecca, the holy site of Islam and the birthplace of the prophet Muhammad. He was profoundly moved by the pilgrimage, and said later that it was the start of a radical alteration in his outlook about race relations.

Upon his return to the United States, Malcolm began to use the name El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz Al-Sabann. He also exhibited a profound shift in political and social thinking. Whereas in the past he had advocated against cooperation with other civil rights leaders and organizations, his new philosophy was to work with existing organizations and individuals, including whites, so long as they were sincere in their efforts to secure basic civil rights and freedoms for African Americans. In June 1964, he founded the secular Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU), which espoused a pan-Africanist approach to basic human rights, particularly the rights of African Americans. He traveled and spoke extensively in Africa to gain support for his pan-Africanist views. He pledged to bring the condition of African Americans before the General Assembly of the United Nations and thereby "internationalize" the civil rights movement in the United States. He further pledged to do whatever was necessary to bring the black struggle from the level of civil rights to the level of human rights. When he advocated for the right of African Americans to use arms to defend themselves against violence, he not only laid the groundwork for a subsequent growth of the black power movement, but also led many U.S. citizens to believe that he advocated violence. However, in his autobiography, Malcolm said that he was not advocating wanton violence but calling for the right of individuals to use arms in self-defense when the law failed to protect them from violent assaults.

In 1965 Malcolm's increasing public criticism of Elijah Muhammad and the Nation of Islam prompted anonymous threats against his life. In his attempts to forge relationships with established civil rights organizations such as the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, Malcolm was criticized severely in the Nation of Islam's official publications. In a December 1964 article in Muhammad Speaks—

the official newspaper of the Nation of Islam— Louis X (now known as Louis

Farrakhan) said, "Such a man as Malcolm is worthy of death, and would have met with death if it had not been for Muhammad's confidence in Allah for victory over the enemies."

On February 14, 1965, Malcolm's home in Queens, New York—which was still owned by the Nation of Islam—was firebombed while he and his family were asleep. Malcolm attributed the bombing to Nation of Islam supporters but no one was ever charged with the crime. One week later, when Malcolm stepped to the podium at the Audubon Ballroom in New York to present a speech on behalf of the OAAU, he was assassinated. The gunmen, later identified as former or current members of the Nation of Islam, were convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment in April 1966.

Malcolm left a complex political and social legacy. Although he was primarily a black nationalist in perspective, his changing philosophy and politics toward the end of his life demonstrate the unfinished development of an influential figure. Although some people point to his identification with the Nation of Islam and dismiss him as a racial extremist and anti-Semite, his later thinking reveals profound changes in his perspective and a more universal understanding of the problems of African Americans. In his eulogy of Malcolm, the U.S. actor Ossie

Davis said...

However we may have differed with him—or with each other about him and his value as a man—let his going from us serve only to bring us together, now. Consigning these mortal remains to earth, the common mother of all, secure in the knowledge that what we place in the ground is no more now a man—but a seed—which, after the winter of our discontent, will come forth again to meet us.

END

Malcolm

X made some great quotes, and I believe was sincere in his efforts to empower

African Americans to fight for justice and equality. Unfortunately,

Malcolm X has led untold multitudes of blacks into the damnable Islamic

religion, which denies Jesus Christ. By the way, the Jewish religion of

Judaism is just as damnable. Islam teaches that Jesus never died on

the cross, is not the Savior, and is not the Son of God. Dr. Kenneth Boa

correctly states...

Malcolm

X made some great quotes, and I believe was sincere in his efforts to empower

African Americans to fight for justice and equality. Unfortunately,

Malcolm X has led untold multitudes of blacks into the damnable Islamic

religion, which denies Jesus Christ. By the way, the Jewish religion of

Judaism is just as damnable. Islam teaches that Jesus never died on

the cross, is not the Savior, and is not the Son of God. Dr. Kenneth Boa

correctly states... Malcolm X, Religious Figure / Civil Rights Figure

Malcolm X, Religious Figure / Civil Rights Figure

Malcolm X described in his autobiography (written with Alex Haley) the harassment of his father, including terrifying visits from the Ku Klux Klan; one of Malcolm X's first memories is of his home in Omaha burning down. The family moved to Lansing, Michigan, in 1929 and there Malcolm X's memories were of his father's rousing sermons and the beatings the minister gave his wife and children. Malcolm X believed his father to be a victim of brainwashing by white people, who infected blacks with self-hatred--therefore he would pass down a form of the abuse he received as a black man.

Malcolm X described in his autobiography (written with Alex Haley) the harassment of his father, including terrifying visits from the Ku Klux Klan; one of Malcolm X's first memories is of his home in Omaha burning down. The family moved to Lansing, Michigan, in 1929 and there Malcolm X's memories were of his father's rousing sermons and the beatings the minister gave his wife and children. Malcolm X believed his father to be a victim of brainwashing by white people, who infected blacks with self-hatred--therefore he would pass down a form of the abuse he received as a black man. In 1963 a conflict between Malcolm X and Elijah Muhammad made headlines. When President John F. Kennedy was assassinated, Malcolm said that it was a case of "chickens coming home to roost." Rolling Stone reported that many people believed Malcolm X had declared the president deserving of his fate, when he really "meant the country's climate of hate had killed the president." Muhammad suspended Malcolm X for ninety days "so that Muslims everywhere can be disassociated from the blunder," according to the autobiography.

In 1963 a conflict between Malcolm X and Elijah Muhammad made headlines. When President John F. Kennedy was assassinated, Malcolm said that it was a case of "chickens coming home to roost." Rolling Stone reported that many people believed Malcolm X had declared the president deserving of his fate, when he really "meant the country's climate of hate had killed the president." Muhammad suspended Malcolm X for ninety days "so that Muslims everywhere can be disassociated from the blunder," according to the autobiography. (1925-1965), black leader. Born Malcolm Little in Omaha, Nebraska, Malcolm was the son of a Baptist preacher who was a follower of Marcus Garvey. After the Ku Klux Klan made threats against his father, the family moved to Lansing, Michigan. There, in the face of similar threats, he continued to urge blacks to take control of their lives.

(1925-1965), black leader. Born Malcolm Little in Omaha, Nebraska, Malcolm was the son of a Baptist preacher who was a follower of Marcus Garvey. After the Ku Klux Klan made threats against his father, the family moved to Lansing, Michigan. There, in the face of similar threats, he continued to urge blacks to take control of their lives.