|

Why Are We

Pushing Witchcraft On Girls?

by Matt Nisbet

Matt Nisbet is Public Relations Director for the Committee for the

Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal (CSICOP). This

article first appeared on the Skeptical Inquirer Electronic

Digest, October 28, 1998.

Sometimes the games that children

play can have serious consequences. On October 20, at a Maryland

high school, fifteen-year-old Jamie Schoonover was sent home from

school with a referral slip noting that she was disciplined for

“casting a spell on a student.” A classmate had accused

Schoonover, an admitted practicing witch and the daughter of a

witch, of placing a hex on her.

The news may sound

bizarre or like something from Arthur Miller’s The Crucible,

but the incident is the latest in a brewing national fascination

with witchcraft. Estimates vary, but there are between 400,000 to 3

million practitioners of Wicca in the United States. Adherents to

the religion, male and female, call themselves witches or Wiccans,

and are actively battling for religious acceptance and tolerance for

their beliefs. Some claim that Wicca is the fastest growing

religion in the country.

In sorting which

witch is which in this matter, anthropologists identify four types

of witches common to popular Western imagination. The “satanic

witch” was persecuted as a devil worshiper during the Inquisition

and the Salem witch hunts, and the image still abounds among

evangelical Christians who warn of the existence of widespread

satanic cults in the United States.

The “tribal witch”

represents the dualism of good and evil magic found in the native

religions of American Indian, African-Caribbean, and Pacific

Islander cultures. The tribal witch is thought to be the opposite

of the benevolent healer or shaman and is often made the societal

scapegoat for ill fortune or hardship. Recent political turmoil in

South Africa and Java have sparked national witch hunts resulting in

hundreds of murders fueled by jealously, fear, superstition and

prejudice. The “fairy tale witch” is the hideous crone found in

fables such as Hansel and Gretal and The Wizard of Oz.

Wicca, however,

falls under the category of what anthropologists call “neo-pagan

witch,” with most Wiccans tracing their origin to pre-Christian

times and Celtic druidism. Wicca has nothing in common with

so-called satanic witchcraft, and Wiccans do not profess a belief in

Satan, but rather in a female goddess that resides within all things

natural. Most Wiccans maintain a belief in psychic ability

including clairvoyance, psychokinesis and spirit communication. The

feminist movement has found an agreeable companion in Wicca, with

the religion’s emphasis on self-empowerment (often through

supernatural means), matriarchal deism, and female spiritual

leaders.

Like many things

in culture straddling the boundary between the mainstream and the

fringe, Hollywood and other sectors of the media, including book and

magazine publishers, have co-opted the rich subject matter of Wicca

and witchcraft into an explosion of books, films and magazine

articles. Currently in theaters is the

sister-story-turned-supernatural-yarn Practical Magic with

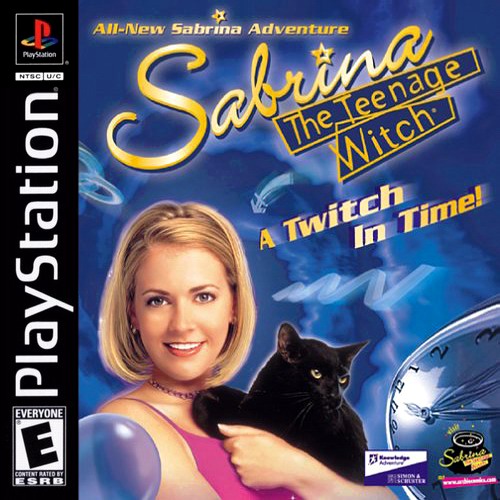

Nicole Kidman and Sandra Bullock. Television has taken notice with

the top-rated ABC sitcom Sabrina the Teenage Witch and WB

Network’s Charmed. Book sales have jumped since the late

1980s, with today’s hottest titles in witchcraft, typically a

combination of memoirs and New Age self-help, approaching 40,000

copies sold. Spin Magazine in its “Grrrl [sic] Power” issue

ranked witchcraft as the top interest among teenage girls. Even

advertisers are trying to charm consumers as Finesse Shampoo, Cover

Girl cosmetics and Camel cigarettes feature witches in their ad

campaigns.

The result is that

the cottage industry of Wicca, by word-of-mouth growth, has been

mutated into the latest Hollywood-driven fad. But do we really need

all this magical thinking? Why are we pushing witchcraft on teenage

girls when we desperately need to be selling girls on science and

math?

Even without the

burden of the magical thinking of witchcraft, long-existing cultural

barriers already hold back girls from performing on equal ground

with boys in math and science. According to a 1992 report by the

Wellesley College for Research on Women, on Advanced Placement exams

girls lag behind boys in math, physics, and biology. On the 1991

SAT, girls scored 44 points lower than boys in math. The National

Sciences Foundation reported that in 1991 girls earned only 29

percent of the science and engineering doctorates awarded in the

United States.

Unfortunately, the

late 1990s is a postmodern world where reality is conceived as

multitudinous, and taken as the latest image flashed across the

television screen or the hottest billion dollar ad campaign to

arrive from Madison Avenue. Parents and schools are responsible for

providing a solid grounding in the sciences and math and for

teaching critical thinking. But the media also shares some of the

burden. Society is constantly and relentlessly bombarded with media

presentations of pseudoscience, fantasy and the paranormal.

Witchcraft is only the latest example of a media-driven paranormal

fad and certainly not the last.

|